Ahmići

48 hours of ashes and blood

This presentation contains material that some viewers may find disturbing.

Prologue

The ICTY and the investigation, reconstruction and prosecution of the crimes committed in April 1993 in Lašva Valley

Tragedy carried out in April 1993 in a small village of Ahmići reflects in a microcosm the much wider tensions, conflicts and hatreds which have, since 1991, plagued the former Yugoslavia and caused so much suffering and bloodshed. In a matter of a few months, persons belonging to different ethnic groups, who used to enjoy good neighbourly relations, and who previously lived side by side in a peaceful manner and who once respected one another’s different religious habits, customs and traditions, were transformed into enemies. Nationalist propaganda gradually fuelled a change in the perception and self-identification of members of the various ethnic groups. Gradually the "others", i.e. the members of other ethnic groups, originally perceived merely as "diverse", came instead to be perceived as "alien" and then as "enemy"; as potential threats to the identity and prosperity of one’s group. What was earlier friendly neighbourly coexistence turned into persecution of those "others".

The main target of these attacks was the very identity – the very humanity – of the victim. The "personal violence" which is carried out against other human beings solely upon the basis of their ethnic, religious or political affiliation.

From the summary of Trial Chamber Judgement in case ‘Kupreškić et al’

Selection of documents

Crime uncovered

In the early morning of 16 April armed clashes broke out between the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croat HVO forces in the town of Vitez. There were also simultaneous and apparently concerted attacks by Croat HVO forces on the surrounding villages. Most of the villages appear to have been defended and combat ensued, with the notable exception of Ahmići.

The village of Ahmići is approximately 2 kilometres east of the town of Vitez in central Bosnia and Herzegovina. Until 16 April, the population was approximately 800, about 90 per cent of whom were Muslim. The village housed an estimated 300 Muslims who had previously been forcibly displaced from other areas.

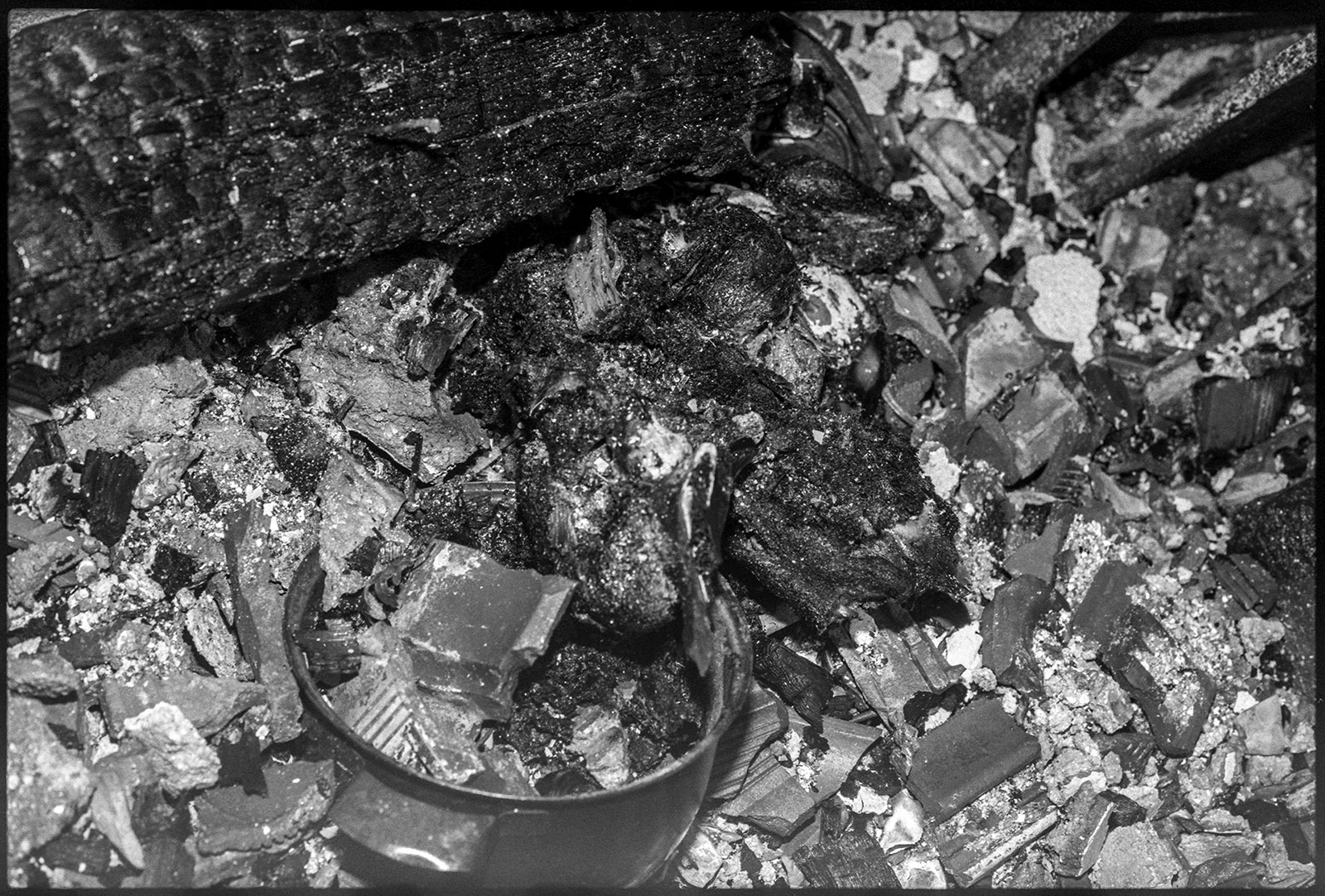

When the Special Rapporteur’s field staff visited the village in early May, some of the approximately 180 destroyed houses were still smoldering, two weeks after the attack. During or after the attack, the two mosques in the village were destroyed, one with explosives; the other was gutted by fire and was still smoldering when field staff visited the village. Of the 89 bodies which have been recovered from the village, most are those of elderly people, women, children and infants. A list of 101 possible victims was obtained through the testimony of displaced persons who had witnessed killings.

From the Mazowiecki Report, 19 May 1993

Selection of documents

Crime in progress

The massacre carried out in the village of Ahmici on 16 April 1993 comprises an individual yet appalling episode of that widespread pattern of persecutory violence. The tragedy which unfolded that day carried all the hallmarks of an ancient tragedy. For one thing, it possessed unity of time, space and action. The killing, wounding and burning took place in the same area, within a few hours and was carried out by a relatively small group of members of the Bosnian Croatian military forces: the HVO and the special units of the Croatian Military Police, the so-called Jokers. Over the course of the several months taken up by these trial proceedings, we have seen before our very eyes, through the narration of the victims and the survivors, the unfolding of a great tragedy. And just as in the ancient tragedies where the misdeeds are never shown but are only recounted by the actors, numerous witnesses have told the Trial Chamber of the human tragedies which befell so many of the ordinary inhabitants of that small village.

From the summary of Trial Chamber Judgement in case ‘Kupreškić et al’

Selection of documents

Denial and cover-up

The denial and cover-up of crimes committed in the wars during the 90’s in the area of the former Yugoslavia was, as a rule, carefully planned and systematically executed, as was their commission. The crime in Ahmići is no exception in that regard. Moreover, it is a paradigmatic example.

After the crime in Ahmići on 16 April 1993, in contacts with representatives of the international community, the political and military leadership of the Bosnian Croats put forward a series of theories and im(possible) explanations – from the crime having been provoked by a mysterious Englishman to it having been committed by the Serbs and even Muslims masked in Croatian Defense Council uniforms. The cover-up continued even after the war, more precisely as of November 1995, when the International Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia issued indictments for the crime in Ahmići. Truth to tell, the Croatian authorities forced the accused to surrender voluntarily, taking measures at the same time to prevent evidence which would contribute to shedding light on the truth about Ahmići from reaching The Hague together with Blaškić, Kordić and other accused. Thus, before the arrival of investigators from The Hague, the archives were moved to places inaccessible to them and meticulously cleansed of compromising documents.

The Croatian intelligence service then went a step further, making efforts to infiltrate the Tribunal and undermine its efforts to uncover the crimes in Ahmići and not only in Ahmići at that. The infiltration of Croatian “moles“ in the Tribunal and its Office of the Prosecutor was done within a secret operation called “Operative Action The Hague“.

Due to the refusal of state structures to provide the requested documents and their efforts to obstruct the work of investigators from The Hague, in July 1999 Chief Prosecutor Louise Arbour asked the then President of the Tribunal to report Croatia to the UN Security Council for failure to cooperate. Although the report was never filed, it remains on record that the Office of the Prosecutor knew what was going on behind its back.

After the change of the regime in 2000, it became quite clear that Louise Arbour had not been laboring under a misconception. The new authorities submitted to the Tribunal evidence testifying to the dishonorable acts of the state structures and efforts to conceal evidence on Ahmići and other crimes committed in BH by the Croatian side.

Selection of documents

Guilty pleas

Denial of guilt was a rule at the Tribunal and admission an exception that proves the rule. Out of the 161 persons indicted for war crimes by the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, 21 pleaded guilty.

With the exception of Dražen Erdemović, who had publicly admitted his participation in the Srebrenica genocide even before an indictment against him was issued, all the other accused pleaded not guilty to all the charges at their initial appearances before the Tribunal’s judges.

That pattern was followed by two accused for crimes in Ahmići and the Lašva Valley: Paško Ljubičić, former commander of the 4th Military Police Battalion of the HVO, and Miroslav Bralo, member of the “Jokers”, an anti-terrorist platoon of the 4th Battalion.

Judicial epilogue

The initial indictments for HVO crimes in the Lašva Valley were issued in 1995. During the following 11 years, seven trials were held before the Tribunal involving 13 accused in total.

Two accused were sentenced following their guilty pleas: Miroslav Bralo in 2005 at the Tribunal and Paško Ljubičić in 2008 in Sarajevo, his case having been transferred to the Court of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The eleven accused who pleaded not guilty were tried in the remaining five proceedings. Tihomir Blaškić surrendered in April 1996 and was tried separately starting in 1997 because the other five persons from the original Lašva Valley indictment were still out of the reach of the Tribunal. Zlatko Aleksovski was handed over to the Tribunal by the Croatian authorities in April 1997 and his trial began in January 1998. Anto Furundžija was arrested by the SFOR in December 1997 and his trial was held six months later.

Following the surrender of a large group of the accused in October 1997, two joint trials were held: one involving six HVO members from Ahmići (“Kupreškić et al.”) and the other of two higher-ranking officials, politician Dario Kordić and the HVO Vitez Brigade Commander Mario Čerkez.